It is beyond question that the peak of excitement of this working day – a Wednesday as any other that could just as well be a Tuesday or a Thursday – was the timeracing experiment between a microwave and a librarian. I namely decided to fetch two flies with one swat and heat up some tea water while I return books and get the highly anticipated Genius Loci of Norberg-Schulz.

So that’s how the tea water timerace works: I excitedly get out of my rather comfortable office chair, go downstairs, set the microwave on 4 minutes, insert my new dotted XXL mug in it, close the white door and head downstairs, pretending as if I was paying a totally regular visit to the library. I stick the three useless books (Lynch and someone else) in the little hole, head to the librarian and ask him to hand me over the Genius Loci. “I believe a book is waiting for me,” I say, waving my red card. “Just a moment,” he replies, paying absolutely no attention to my TIMERACE WITH THE MICROWAVE. “Okay, play it cool,” I tell myself, “the water ain’t boiling yet.” 20 seconds later the guy takes my card and hands me the book. “Thanks,” I say, and head back upstairs, very much weary of the two feet beneath me firing up speed. “Hold them’ horses,” I whisper, and deliver a totally regular walk up until the microwave-room. I push the glassdoor and a glance from a distance brings me the biggest joy of the whole day (if not, of the entire week) -the microwave is still on. I nearly jump out of happiness! But no, I get control of my emotions and pretend as if I was down for some casual water-heating business. I open up the teabag and fill the remaining 30 seconds. Yet deep inside I feel a profound sense of victory and glory for having won this battle.

Anecdotes apart, time and rhythms are fascinating. Haven’t we all felt the stagnation of time during the after-lunch hours of a Monday? Or how quickly it melts away on a date with a new loved-one? Best of them all is losing all notion of time – that is, becoming unaware of the minutes, hours, days, and above of all – the week that structures our life. Why does Tuesday feel different from Friday? How come there are seven days a week, and not twelve? Why are suicide rates highest on Monday? These are some of the questions Eviatar Zerubavel tries to answer with his fascinating ‘sociology of time’, The Seven Day Circle (Ref.1) that is a comprehensive look at the religious, political, and economic origins of the week, its cultural variations, and its impact on both society and the individual.

The second chapter of the book might result to be of special interest for those who every now and then feel the urge (like me) of rebelling against the 24/7 system. Zerubavel elaborates rather well on what he calls the “Seven Day Wars”, first of them to take place in France during the French Revolution and the second in Soviet Russia back in the 1930s. In the first case, a new Age of Reason was supposed to be inaugurated with the Ten-Day Décade. The decimal system was conceived as a way of promoting clarity and precision; even though the real target of the reform campaign, was not the astrological but the Christian seven-day week that was abolished to stop traditions related to religion. The Ten-Day Décade did not withstand long against the seven-day week habit -barely 12 years passed from it’s institutionalization in 1793 until the official Sunday rest – along with the Gregorian calendar — was legally reinstated in 1805.

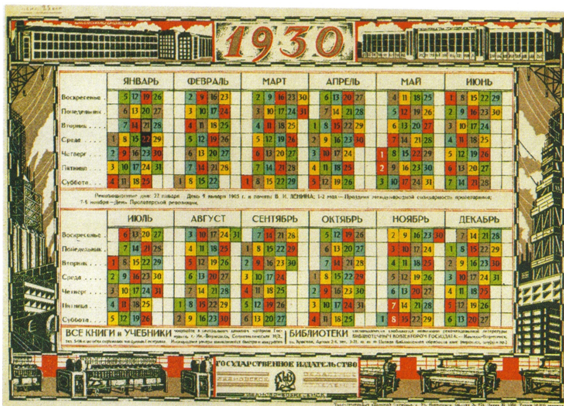

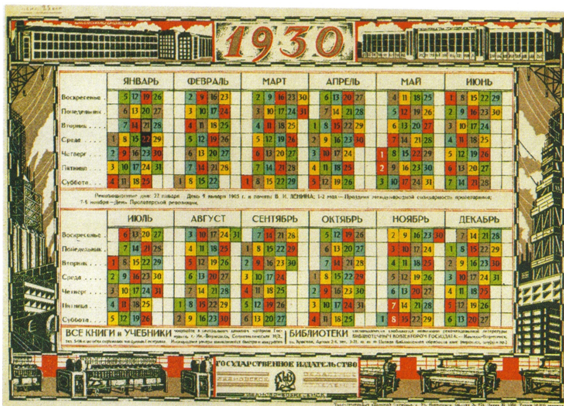

The Soviet time experiment wasn’t much more successful. On August 26, 1929, the Council of People’s Commissaries of the Soviet Union announced that the transition of all productive enterprises as well as offices from the traditional interrupted workweek to a continuous production week would be put into effect. The first alternative time division was the five-day Nepreryvka that would soon be substituted by the six-day Chestidnevki. The introduction of a continuous working day, based on a multiple-shift system that allowed production to proceed 24 hours a week (be it 5 or 6 days long) also hid the aim of destroying religious practices that were not convenient for the Soviet rule and that were based on the seven-day week. However, as in France 140 years earlier, it was the essentially traditionalistic rural population who spearheaded the movement to preserve the seven-day week. The Soviet calendrical adventure finally came to an end on June 26, 1940, when the seven-day week was restored, once again, with the aim of increasing production.

A calendar from the Russian Nepreryvka intent of turning common time measuring into an uninterrupted 5-day work week. Different colors stand for the day off for each individual; red background with white numbers marks national holidays-the only days when the whole country was off duty. The uninterrupted week was supposed to increase industrial production but quickly proved to have contrary results.

Two main ideas can thus be drawn from these intents of modifying time counting: firstly, that official time measuring has been strictly associated to productivity (and its growth) ever since the Industrial Revolution. Time is money, therefore every wasted second equals a loss in profit, equals little growth, equals stagnation. Secondly, both “Seven Day Wars” proved that time counting is very strongly connected to religion, hence to traditions, thus ignoring the ‘common sense’ of time means ignoring common habits and customs, possibly leading those who dare follow alternative rhythms to obtaining a certain reputation of an ‘outsider’. This reminds me of a beautiful observation Cameron makes in his article on jazzmen’s habits back in the 1950s.

We have seen that the jazzman is isolated from persons in general society in several important ways. His time is organized differently-he sleeps while they work, works while they play, and plays while they sleep. (Ref.2)

In one way or another, professionals who do not necessarily follow the 9 – 17 rhythm may become “isolated from persons in general society”. Or adapting to that common rhtythm may cause a sense of being smushed between the iron wheels of the mechanical clock that declares the most efficient periodicity. It is interesting to consider the effect of the pendulum clock whose loud second-counting stamps the rhythm into its listeners; or the role that church bells have in small towns, announcing the passing of each quarter of an hour. Time is all around us and despite its abstract character and individuality of perception, we often seem to be reminded of it ‘running out’, as if time were yet another product on the market.

To finish up, here’s a rather interesting cuckoo clock I found on youtube. Adolf Hitler announcing (whenever he pleases) that it’s two o ‘clock.

(Ref.1) Zerubavel, E. (1985) The Seven DayCircle. The History and Meaning of the Week. New York: The Free Press.

(Ref.2) Cameron, W.B. (1954) Sociological Notes on the Jam Session. Social Forces, Vol.33, No.2. Pg.180.